Chartres, France

April 24, 2000

Like Johann Pachelbel, Jonas Salk, or Monica Lewinsky, some people are known for only one thing. So are certain places.

Giza conjures the pyramids. Agra evokes the Taj. Green Bay means the Packers.

And Chartres summons its cathedral.

We said goodbye this morning to Château de Tertres, and wound our way toward Paris. En route, we made a pilgrimage.

Ours was by no means the first. Tradition has it that the Virgin visited in person, and subsequently drew the lame, sick, or blind, making Chartres something of a Lourdes on the plain of Beauce.

Sandwiched between the Loire and the Seine, this province is a granary of France. Driving north from Blois, fertile fields extend indefinitely in every direction. Rapeseed, wheat, and maize lend variation in color to the soothing monotony of the persistent prairie.

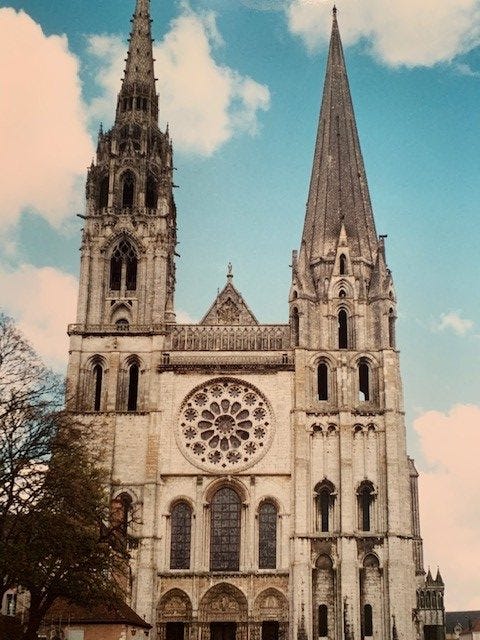

After a couple hours, like Sherif Ali approaching Lawrence at the desert well, a small silhouette appeared on the distant horizon. It slowly grew, and became more ethereal as it advanced.

Spires pierced the sky, providing stark relief to the tabular topography. The approaching cathedral was almost unreal. It sprouted suddenly from the vast expanse, like the Emerald City from a field of poppies.

As the wind wove thru the wheat, the church seemed to waft above the wisps. On this clear day, we expected clouds to form over the shrine, if only so they could part luminously from above.

We discarded our map. It was no longer needed. Medieval bishops and builders erected this church in a style and site such that even (or especially) the most lost would find it. Like an Everest in Kansas, this shrine couldn’t, and wouldn’t, be missed.

Evidence indicates that at least as far back as the Carolingians, Chartres was a pilgrimage site in devotion to Mary. As Marian affection grew, the town’s cathedral became home on earth for the Queen of Heaven.

Blanche of Castile, wife of Louis VIII and mother to St. Louis IX, helped finance the building of Nôtre Dames de Chartres, and egotistically influenced the stained glass depicting Mary as a stately queen rather than a humble virgin.

We approached tentatively, as if in awe. Perhaps because we were.

The building we were about to enter is almost entirely intact from about 1260. Some of it is even older. In 1194 a fire gutted the nave of the previous church, leaving only Bishop Fulbert’s subterranean crypt, plus the façade and south tower of the distinctive west front.

The blaze ostensibly consumed almost every house in town. The current cathedral bears its scar, but is not diminished by it. This edifice, in its structural foundation, artistic features, and architectural form, is remarkably well-preserved.

The spire atop the north tower, Le Clocher Neuf, seems incongruous with the rest of the church. The preceding steeples each succumbed to fire. The current incarnation rose in 1506. It is among the few facelifts to which this distinguished lady ever felt need to concede.

The surgery was perhaps too elaborate. Its ornate Gothic design is intricate, delicate, and beautiful. But its flamboyance clashes with the understated dignity of Le Clocher Vieux to the south, and undermines the unity of the more austere façade.

Supreme among surviving treasures are the sublime statuary and exquisite stained glass. The quantity and quality, around and throughout, are astounding. I certainly can’t absorb, or describe, them all.

Fortunately for us, at the cathedral today was Malcolm Miller, for three decades a renowned Chartres scholar and guide. He gave us a tour, and sold us his book. They added facts and figures to the feelings and fancy that inform these notes.

In and on the church, more than 10,000 carved or pictured images portray saints, sinners, angels, and demons. Two thousand statues grace the portals alone. Those guarding the transepts are phenomenal.

Almost 800 surround the south entry, which centers around Christ on His seat of Judgement. Over these doors philosophers mingle with the saints. Music is personified in Pythagoras, Dialectic is embodied in Aristotle, and Rhetoric carved into Cicero.

The north portal is devoted to Mary, and its sculpted figures – including her mother, St Anne, on the trumeau of the central bay – are without equal. Henry Adams called them “the Aeginetan Marbles of French art.” In the round they express the flowing ease of Greek sculpture rather than the tense stiffness of most Medieval statuary.

But the sparkling jewels are embedded within the crown. Coloring the simple vault over the nondescript nave, illuminating the ornate tracery of the superb choir screen, and embellishing the distinctive entrance labyrinth, is the story of Medieval France, as told by the light of 3,900 stain glass figures depicted in 174 impeccable windows.

Finest of all, and perhaps predating the 1194 fire, is Nôtre Dame de la Belle Verrière. Our Lady, and her window, are indeed beautiful. But, for this Queen, one masterful pane does not suffice.

Within the west wall, and coating the nave in soft tones and sundry shades, is a forty-four foot Rose that has been called the finest glass known to history. I wouldn’t know. But I wouldn’t doubt it.

Complementary petals adorn each transept, flooding the sacred chancel in divine light. On the north side, Louis XI and Blanche of Castile dedicated to the Virgin “The Rose of France.” It is opposed on the south by “The Rose of Dreux”, in honor of her Son. Both filter heavenly hues into the cathedral air.

It is hard to imagine such sublimity being inconsiderately disturbed, or intentionally destroyed. But when a man enters a crowd, he exits civilization. The greatest threat came, as it has to most churches in France, from Jacobin jackasses.

In 1793, the revolutionaries rededicated the cathedral as a “temple of reason”, burned the wooden statue of Our Lady of the Crypt, and threatened to dismantle all other statues, inside and out. Some suggested demolishing the entire church. The building obviously survived that lunacy, as well as that of the second world war.

Barely.

Allied bombs destroyed much of the surrounding town. Miraculously, the cathedral was spared. Its precious glass was dismantled, and thereby preserved. But an astute American colonel saved the rest of the church by questioning a chilling American order.

Thinking the Germans occupied the structure, the American military, with customary government sensibility, ordered it destroyed. Pleading with his “superiors” not to do so, Colonel Welborn Griffith volunteered to go inside. Confirming the church was empty, he rang its bells, signaling a safe harbor for his troops – and saving the cathedral for us. The destructive order was called off.

Like the town by which he is honored, Colonel Griffith will forever be known for only one thing. And he did it just in time.

He died in combat later that day.

JD